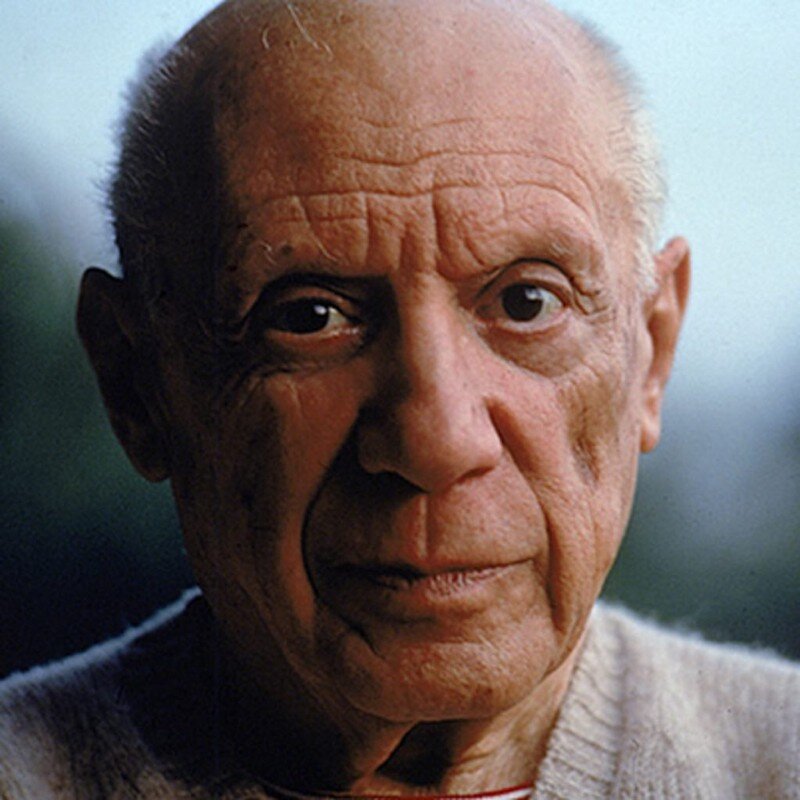

9 Things I Learned from Pablo Picasso

The name “Pablo Picasso” has become synonymous with creativity so much so that the Spanish painter has reach an almost-mythical quality. But what factors play into the master’s genius? And what can we learn from it?

1) Pablo’s self confidence was off the charts

I mean you probably could have guessed that, right? Despite what you do or don’t know about the old master, you probably could have guessed the guy felt pretty solid about himself.

What you may not know is the extent to which this was the case.

Our striped-shirted Spaniard once walked into the Louvre in Paris carrying his own paintings. Imagine strolling up to the Hollywood walk of fame and saying, “Yep, I’ll just start carving my name here. Whenever you guys want to make it official, let me know.” Picasso had this much confidence in himself.

Why? Because, yes, he believed he belonged there.

(Please note — his belief came first, then the work.)

[For the video lovers…

]

2) Love matters

Picasso was an artist coming of age in the early 1900s — a time when modern society would get many ideals about what it would mean to actually fundamental be an artist. This is opposed to just doing art, which is part of the human experience for everyone. Many norms, stories, and expectations would be set by how the group of artists acted during this time.

“How they acted” in this case meaning “how many people they slept with.”

Picasso had a number of mistresses, lovers, flings, and flirts. To say Picasso jumped from lover to lover throughout his lifetime would be like saying that a frog sometimes hops to get where he is going.

However, it is worth pointing out while Picasso was carving out Cubism — probably his most important contribution to the artistic scene as a whole — he spent the majority of his time with one lover — Eva Gouel. Eva was as close as Picasso would ever get to a committed relationship, as they were madly in love between the years of 1911 and 1915.

Coincidentally (or not) Picasso’s fierce affection with his live-in flame matched up with the time in which Picasso created the movement he is most known for.

Records show that Picasso was absolutely crippled by Eva’s early death by tuberculosis, and he never had a firm relationship from that point forward. And although he continued to paint, he never reached a similar break though.

So Picasso, probably one the greatest painter to hold a brush, had a deep affectionate connection during debatably his period of biggest impact.

And you are trying to do your thing alone?

3) Changed his Name

Okay, we went over this briefly with Einstein and how there is no chance anyone remembers a physicist named Albert Schleppelhorf.

However, Picasso adjustment to a more memorable name was a *bit* more dramatic. Picasso’s full name is (deep breath here)

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso

Can you imagine his mother shouting after him when he was in trouble?

However, it’s worth pointing out that Pablo Picasso was Pablo Ruiz for the first 20 or so years of his life. Whether because he was aware the Ps and the Os bracketing each name would help cement his legacy or whether it was because he dropped the Ruiz because of the strained relationship with his father, we might never know.

The name you are known by is part of your creative marketing. Aubrey Graham is Drake, Peter Hernandez became Bruno Mars, and Stefani Germanotta became Lady Gaga. And Pablo Ruiz, a common and forgettable Spanish name becomes Pablo Picasso, an alliterative and sticky label which flows off the tongue.

Don’t like your name? Change it.

4) Powers of Two

When a creative person is on the edge of a breakthrough, he needs strong support in two different areas:

Affective support — as in, someone who loves the creative no matter what

Cognitive support — as in, someone who can criticize, complement, and/or improve the breakthrough in progress.

The two of these support systems collide in letting the creative know that a) he is loved despite his crazy ideas and b) he is not losing his mind. You already know Eva was by his side, providing the first half of the support needed for the Cubist movement. Now, for a name you might not know — George Braque.

Braque contributed just as much to the cubist movement as Picasso (if not more). The two men worked side by side, day in and day out. Braque was the technician to Picasso’s free thinking, the meticulous thinker to Picasso’s emotional feeler, the yin to his yang.

Painting, like writing, is a intensely personal activity. Execution of any idea requires an incredible amount of solitude and isolation. Unlike dance or music, there are no real quick corrections. Braque didn’t stand over Picasso’s shoulder. Instead, the two men would spend all morning painting, and then spend all evening examining each others work.

I don’t want to be unclear — without Braque, you probably don’t know Picasso’s name.

Every artist needs a muse. But they also need a logical voice who is not emotionally attached to the work.

Unfortunately, when Braque went off to fight in the first world war, he and Picasso fell out of touch and eventually, out of favor. This seems to be an ugly pattern in our master’s life, which leads me to…

5) NOT a people person

Ugh, this is awkward, right?

You don’t want to think someone as brilliant and talented and sweet looking could be mean. Yet most reports lend to a picture of a man with downright disregard for other human lives. In a worst case point of view, it’s possible he derived some sort of pleasure or creative people from making others uncomfortable. Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner even used the word “sadistic.”

Yikes.

However, I am the type of person who looks for the best in people… even reportedly awful ones.

Even if you did know Picasso turned into a jerk, what you may not know is just how early his childish naivete was ripped from him.

At age 12 Picasso’s younger sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria. When a person contracts diphtheria, they often develop a “barking cough due to a blocked airway.” This was 1900. What does this mean? It means Conchita Ruiz actively and loudly coughed until the moment she could no longer breathe. She did this in the middle of the family home.

Can you imagine waking up in the middle of the night to hear your younger sister’s rattling coughs echo through the house? Can you imagine seeing your playmate’s clothes stained with blood? Can you imagine everyone in the home counting down the days, wondering how many more she would have?

This was not exactly an easy burden to bear.

Yes, Picasso treated people poorly. No, it is never that simple. This event was only the first item in Picasso’s collection of demons. It would later grow when a good friend Casanagus put a bullet through his head. Losing his lover Eva couldn’t have helped.

In spite of these great tragedies (or more likely because of it) Picasso found fuel for work which will never be forgotten. He also became an insufferable and hateful old man.

Was it worth it?

Probably depends on who you ask.

6) Starting young helps

Okay but before you get all swept away in the baby genius thing, can we talk about what the word “prodigy” means for a minute:

“A person, especially a young one, endowed with exceptional qualities or abilities.”

This definition is misleading although typical of how we think about talented youth. That word “endowed” itself has a bit of a magical quality, as if a billion stars aligned to gift the planet with a ONE TRUE ARTIST.

Are there ingenious children? Sure. But history often skips over other supporting factors: Mozart’s dad was already a musical expert. Tiger Woods’ father had the time and information to turn the young talent into a global star, and with a whole family already entrenched in the music industry, of course Michael Jackson became a breakout hit at age six.

Likewise, Pablo’s father was already an artist himself, although reportedly a bad one, and was able to provide the tools and support the budding painter needed.

I love what choreographer Twyla Tharp says on this topic:

“Often destiny is a determined parent.”

Nevertheless, legend has it that young Picasso’s first word was “La Piz” (pencil), and that he was already drawing very good work at the age of 9, and progressed exponentially throughout his teenage years.

It’s nice when your career starts 10 years before that of your contemporaries. Often there is no substitute for time.

7) Law of attraction

Okay, riddle me this one:

Pablo Picasso grows up in Málaga, Spain. He speaks almost no French. Yet, in 1900, he moves to French and instantly befriends a poet, Max Jacob.

Despite having zero connections and almost no way to communicate with anyone when he moved there, Picasso becomes close friends with both powerful friends and talented artists, including Gertrude Stein in the former category and Henri Matisse in the latter. Year after year, his web grows.

I am sure there is a logical and sound explanation for this, but here is mine:

The Law of Attraction.

When a single ideal consumes all your waking thoughts and actions, your connections and growth ascends language, social status, or other barriers. Picasso was about painting. He was also very good at it. When you remove all other pesky variable (like, say, not being able to speak to anyone), it seems almost inevitable people would flock to see a master at work.

(We actually can get a sense of what watching Picasso might have been like. This video of the master at work is mesmerizing.)

8) Personal symbols for universal themes

You get the sense there was almost no boundaries between life and the canvas for Picasso. From the death of his little sister Conchita to the suicide of Casagemus to the grief felt by an nation in the devastation of the Spanish Civil War, Picasso left nothing unsaid. Or rather, nothing unpainted.

Good artists can create something and explain what it means.

With great artists, no explanation is necessary.

9) Quantity of work

Yes, Picasso had natural talent.

Yes, Picasso had a father who was an artist (and therefore gave the boy a head start).

Yes, Picasso was given many lucky breaks along the way.

Do you know what else he did? Painted at least 300 canvases every year. Pablo lived to 91. We can guess he started this pace somewhere around the age of 17 (likely sooner). That’s over 20,000 paintings.

I dare you to participate in your art half that many times and see how “naturally talented” you become.

This is #2 in a series: Learning Creativity from the Masters. Here is another: